Caravaggio’s Fortune Teller – a painting about the dangers of life and the illusion of art

Caravaggio’s The Fortune Teller, Musei Capitolini - Pinacoteca Capitolina

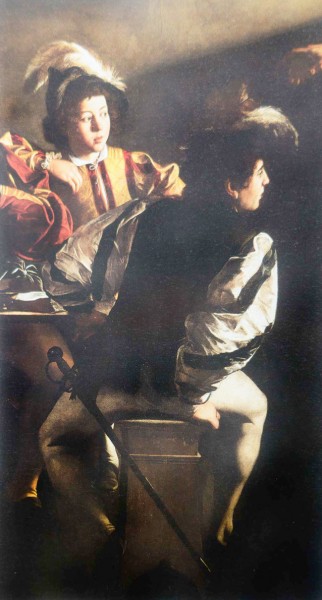

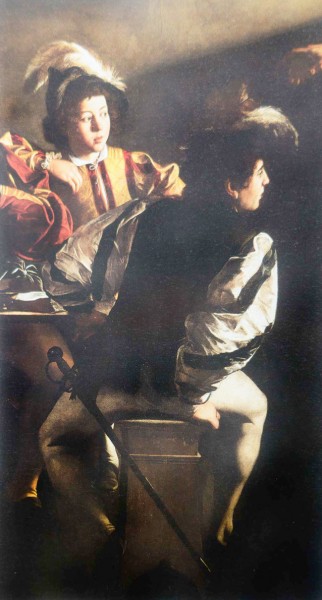

Caravaggio’s The Fortune Teller, fragment, Musei Capitolini - Pinacoteca Capitolina

Caravaggio’s The Fortune Teller, Musei Capitolini - Pinacoteca Capitolina

Caravaggio, The Calling of Matthew as an Apostle, fragment, Contarelli Chapel, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi

Caravaggio’s The Fortune Teller, Louvre, Paris

The outstanding Italian art historian Roberto Longhi (who discovered Caravaggio) claimed that there was nobody who could better impart the reality of life than a young artist just entering it, taking in everything that surrounds him. What was it that the over-twenty-year-old Caravaggio who came from Lombardy saw on the streets of Rome? A never-ending crowd of young men, who similarly to him came to the city on the Tiber in search of work, adventure, and fame. There were also a few women – servants, laundrywomen, street vendors, prostitutes, procuresses, and finally Gypsies, looking for young and inexperienced "prey" since they easily gave in to temptation.

The outstanding Italian art historian Roberto Longhi (who discovered Caravaggio) claimed that there was nobody who could better impart the reality of life than a young artist just entering it, taking in everything that surrounds him. What was it that the over-twenty-year-old Caravaggio who came from Lombardy saw on the streets of Rome? A never-ending crowd of young men, who similarly to him came to the city on the Tiber in search of work, adventure, and fame. There were also a few women – servants, laundrywomen, street vendors, prostitutes, procuresses, and finally Gypsies, looking for young and inexperienced "prey" since they easily gave in to temptation.

A young, smiling Gypsy is holding the palm of a young man in one hand, while with the other she delicately brushes his fingers. However, she is not looking at the palm of the well-dressed client, whom she probably foretells an extraordinary future, career, or love, but rather, deeply looks into his eyes, as if she desires to enchant him. He, on the other hand, unable to avert his eyes, charmed by her words, but also by the warm touch of her hand, does not notice the game which is being played and of which he is the victim. The Gypsy removes a ring from the boy's finger. Therefore, we can ask, does the youth represented in the painting want to know his future, or is he rather searching for love and adventure, which can be testified to by his other hand slowly moving to the hilt of his rapier? Caravaggio was well-aware of the fact of how easy it was to become less than virtuous in Rome, where love is bought in second-hand brothels and dark alleys, while thieves and tricksters ferret out inexperienced travelers. At that time, he himself lived in a rented room on the Piazza di San Salvatore in the poor Campo district. In the population census from 1566, the inhabitants of the region were described as "low-born, dishonest, with very many prostitutes, and some Jews”. Prostitution similarly to gambling was disfavorably seen in the city, but while sinful and with numerous bans placed upon them, they were tolerated. But what about palm reading and divination? It was the same. The bulla published by Pope Pius V n 1566 (The Roman Catechism, lat. Catechismus ex decreto Concilii Tridenti ad Parochos) clearly confirmed the sinfulness of such practices. Gypsies who appeared in the Eternal City only a century earlier were not favorably looked upon. They were seen as vagabonds, cheaters, thieves, and beggars. Gypsy women, on the other hand, were treated much better by the naturally superstitious Romans, and sometimes they even aroused curiosity - with their appearance, the magical abilities attributed to them, and their erotic charm.

We could therefore say that Caravaggio created a kind of a morality play depicting the dangers of young life and warning against sin and theft of not only the ring but more appropriately virtue. Thoughtlessness should be punished, while earthly pleasures should be resisted, that is what representatives of the Church would have said. The moralists of that time, on the other hand, without too much difficulty would describe the beauty and youthfulness of the boy, as attributable to virtue. Yet, Caravaggio was much more refined and sly. His Gypsy is not an ugly, old crone, which would clearly depict her as evil as that is how it was personified in the paintings and literary works of those times. She is pretty and well-dressed, we do not see any of the dirt of the street in her, and she is not dressed in rags – it rather brings to mind actresses playing the roles of Gypsies in street and courtly performances, or the heroines of poems going around in the city, in which they were shown as temptresses and refined thieves. Caravaggio had to be aware of those works popular at that time – fleeting texts written in verse, full of comedy, and the grotesque, but also of gypsy intrigues, trickery, and lies. This kind of literary genre even had its own name – “la zingaresca”. Gypsies were also present in the repertoire of commedia dell’arte, joining the ranks of somewhat diabolical characters.

Telling the future, which is what Gypsies dealt in, had to intrigue, since it was a portal to another world – unreal and enchanted, one in which everything was possible. Because what is really happening in the painting between two very similar to each other (in age, physiognomy, and even the color and selection of elegant clothes) young people? They are joined together in a sort of a pact – he in reality is not interested in palm reading and agrees to the Gypsy’s deception, which he could easily notice if he had wanted to, while the Gypsy recognizes this fact and only pretends to be reading his palm. Everything that takes place between them is simply a game, and we are also fooled into believing that the young man is a naïve visitor, while the Gypsy – is a fortune-teller. The painter takes the scene out from the context of the street and sets it on a neutral background while at the same time “moving” the figures towards the viewer, which makes it seem as if they are “about to come out” of the painting bestows an almost theatrical character onto the representation. The protagonists who are almost of natural size seem to find themselves within our reach. We can eavesdrop on them without the fear of being punished, and feel the intensity of their gaze, and the delicateness of their touch. We can and want to fall under the Gypsy’s spell. Being thus charmed we lose the acuity of our vision and the barely visible ring remains unnoticeable. Is the Gypsy really removing it from his finger, can we be certain or is it just an illusion? In this way, playing with our senses, Caravaggio makes us feel uncertain – we see but we do not notice.

In 1603 the poet Gaspare Murtola dedicated a madrigal to this painting, in which he brought together the trickery of the Gypsy with the illusionist painting manner of Caravaggio, suggesting that both the youth and the onlooker are a victim of the trickery. Talking directly to the artist he stated: “I do not know who is the better magician, the woman you depict, or you who paint her”. As we can see Caravaggio’s contemporaries saw in the figure of the Gypsy a personification of art, which deceives and tricks, in this way fulfilling the desire of the viewer.

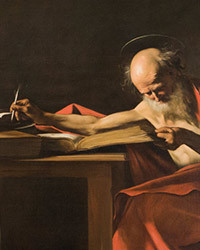

Taking a topic from the Roman street and bestowing a moral message upon it was until then something unheard of in Roman art and had to make an impression on the great admirer of art that was Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. This expert collector and sensitive erudite most likely noticed in the painting something more than a genre scene. He saw a play of meanings that provided the opportunity for limitless interpretations and discussions, a novel approach to the subject, modernity of composition, and the talent of an artist, waiting to be discovered. And thus del Monte gave in to the charming beauty of Caravaggio's painting. He bought the painting rather cheaply in a shop belonging to Constantino Spada, found near his palace. Its author on the other hand found lodgings and protection in the cardinal's palace. Caravaggio's fate had changed – from an unknown painter, one of the hundreds looking to find luck in the city on the Tiber, he became the protégée of an art expert, in whose home he stayed for several years. During that time he painted the world of the streets, inns, and Roman alleys – a theatre of life in which the main roles were played by tricksters, cheats, gamblers, prostitutes (both male and female), but also pilgrims and saints.

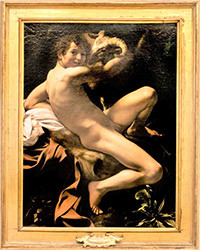

Caravaggio painted the same motif once again. The second, slightly smaller version of the painting is found in the Louvre in Paris.

Caravaggio’s The Fortune Teller, approx. 1595, oil on canvas, 115 x 150 cm, Musei Capitolini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !